Is This What Normal Feels Like?

Despite hurdles, many are hoping for the first ordinary school year since the start of the pandemic

On paper, little about the upcoming school year felt settled in the weeks — and even days — leading up to September 8, the start of classes for many students in Manhattan. Would bitter negotiations over the city’s education budget end amicably? Might COVID-19 again put a damper on in-person learning? Or could this be the year that schooling returned to normal?

“There’s always that moment, when the weather starts to turn and it’s back to school time, and you just sort of feel it,” Upper East Side Council Member Julie Menin said. “Just from the chatter, like when I take my daughter to the playground or just speaking to other parents, people are now excited about this. It’s been a long, long slog — it really has. And now I think people are ready for a new phase and getting back to the new normal.”

The first morning at P.S. 87, on the Upper West Side, there was no hint of uncertainty among the crowd of students and parents. Hardly a mask in sight, adults chatted in a line that wrapped around the block. They rounded up kids for first-day-of-school photos and sent them charging toward their school building. “Have a great day!” one parent yelled to a child who had nearly made it out of earshot.

Despite a drawn-out political battle over public school funding, many are hoping for the ordinary. But the pandemic has proven to be not so distant of a memory.

Fewer Kids – And A Fight For Money

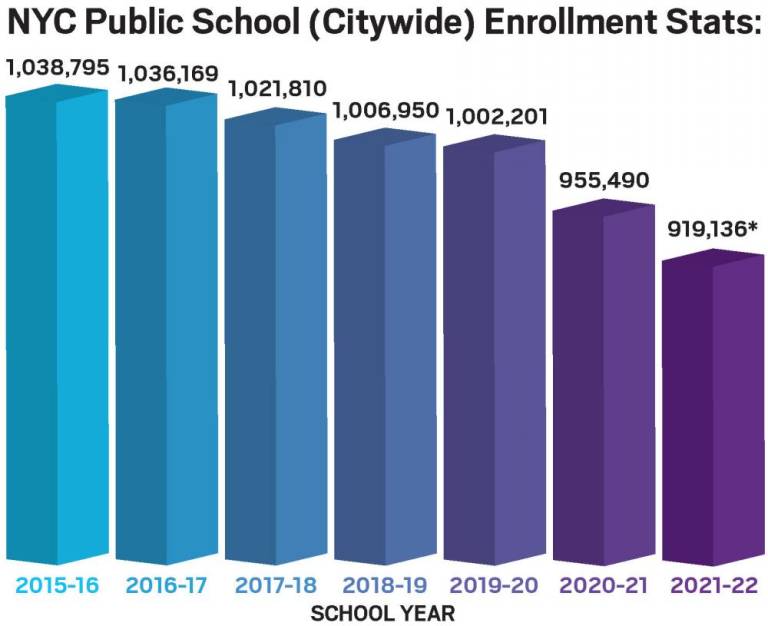

Fewer and fewer kids are being enrolled in the city’s public schools, a trend that started years before the pandemic — but only intensified during COVID-19’s reign. The number dropped every year since the 2015-2016 school year, when 1,038,795 students were enrolled, data from the New York City Independent Budget Office shows. By the 2021-2022 academic year, that number had dropped to 919,136, a Department of Education spokesperson told Our Town.

The dwindling pack of public school students, the agency said, could be attributed to the pandemic, or to “population shifts and stalling birth rates.” Others suspect the state of schools might have something to do with it. “Public schools have to do a better job of drawing people” in, Upper West Side Council Member Gale Brewer told Our Town. If attractive programming isn’t funded, she hypothesized, “then people are going to leave even more to go, in our district, to private school or to charter school.”

But it was declining enrollment numbers that Mayor Eric Adams’ administration cited as justifying deep cuts to the city’s education budget. The exact amount of those cuts has been a point of contention during the negotiation process. Rather than a drop of a little over $200 million, New York City Comptroller Brad Lander has estimated the slash could actually top $300 million.

Despite an initial vote of approval on the FY 2023 budget in June, a number of City Council members quickly changed their tune. “It has become clearer than ever that DOE lacks transparency and accountability and removed hundreds of millions of dollars more from school budgets than it ever conveyed in the city budget,” City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams said in an August statement. Recently, Brewer noticed what she believed to be a larger number of teachers who had appealed being “excessed” from their schools, meaning they were supposed to be out of a teaching position — though she said it’s “hard to know” whether it was the direct result of budget cuts.

In early September, the City Council voted unanimously (and mostly for show) to pass a resolution calling for the reinstatement of $469 million in funds for the city’s public schools — only two days before they opened their doors for the new academic year. A lawsuit seeking to reverse the budget decision has also been in limbo. “This has to get resolved,” Menin said, “and it has to get resolved very, very soon.”

The Pandemic Years Didn’t Feel Real

While some are looking forward, others are still grappling with the past. During the pandemic, public housing activist La Keesha Taylor noticed that her two sons, 7-year-old Ethan and 11-year-old Anthony, were struggling to stay on course. Both have Individualized Education Program accommodations for their learning needs; after being diagnosed early, Anthony’s ADHD worsened in third grade, coinciding with the pandemic. “He’s not moving up, he’s having trouble,” Taylor recalled of his experience.

It wasn’t just Taylor’s kids. Students with learning differences had a tough time with virtual learning during the pandemic, explained Dylan Bitensky, a tutor and clinical psychology master’s student at Columbia University. One seventh-grade student she tutors on the Upper East Side, who has dyslexia and ADHD, told her that Zoom classes didn’t feel “real.”

“You can’t really show someone how to do math when you’re explaining it over Zoom,” Bitensky said. “And especially someone who has dyslexia or ADHD, you need to see what you’re writing and have someone actually touch the paper, so your attention goes there.” The long-term impact of years lost to online learning has yet to fully reveal itself. “A lot of kids don’t even remember when their classroom was fully not remote,” she added.

In public schools, Taylor believes certain changes — like further restricting class sizes, ensuring that there are two teachers in each classroom and providing free after-school programming at all schools — would benefit young students and families. “There’s always money that we’re not using that we’re saving for a rainy day,” she said. “But guess what? There’s holes in our roof and it’s raining now.”

A New Outlook On “Normal”

In some pockets of Manhattan, the sun’s already out — or the storm clouds are at least beginning to clear. Menin’s Upper East Side district saw a 6% total decrease in school funding totaling $3.4 million (the budgets for five schools increased by an average of $216,000; 12 schools lost an average of $372,000 each). But the council member managed to secure $11.4 million for district schools, including via participatory budgeting — an enormous increase over last year’s $2.4 million allocation.

She’s still aiming to build a new public school in the district, a long-held goal. Funding, Menin said, has already been promised; Now, she’s searching for the physical space.

At Notre Dame School of Manhattan, a private, all-girls Catholic high school in the West Village, the year ahead looks bright. Enrollment has remained steady — and at capacity, with around 360 students — for the last few years, according to Jackie Brilliant, the school’s communications and outreach coordinator. “This year, our most ‘normal’ re-opening in several years, feels both joyful and routine,” she told Our Town.

At Bank Street School for Children, a private Upper West Side school that teaches preschool through eighth-grade students, enrollment has increased in the past two years, according to Head of School Doug Knecht. “We’re seeing lots of smiles,” he wrote in a statement, describing the start of classes.

Teachers and students alike, both schools have found, are eager to lean back into their usual routines. “Now we all get to enjoy and appreciate what we might have taken for granted before,” Brilliant said.

“It’s been a long, long slog — it really has. And now I think people are ready for a new phase and getting back to the new normal.” Council Member Julie Menin