Katharine Graham’s New York Story

New-York Historical Society’s new exhibition captures the impact of the legendary news executive

In the middle of the Reagan administration, in the social whirl of a Washington, D.C., now long vanished, Ben Bradlee and Sally Quinn hosted a farewell party for a young couple, both journalists, headed off to cover India.

Cabinet secretaries, famous journalists and social swells crowded the Georgetown event. “I was the only person there I had never heard of,” one guest recalled, relating the event years later.

Yet the high spirits concealed a gendered power struggle that had nearly blocked the cause of the celebration. The honored couple, Steven R. Weisman and Elisabeth Bumiller, worked for competing publications, The New York Times and the Washington Post.

A.M. Rosenthal, the legendary editor of the Times, had asked Weisman, White House Correspondent , to become Delhi Bureau Chief, a job Rosenthal himself had held. But Weisman’s new spouse, then a star in the Style Section, The Post’s still fresh reinvention of what had previously been the “women’s” section, could not possibly continue writing for the Post and compete with her husband or The Times, Abe Rosenthal insisted.

But the Post and Bumiller stood up to Rosenthal, who eventually relented. Bumiller could write for the Post, after all.

The party was on. Toast after toast was offered and then, just as the bar was about to reopen, Bradlee realized that one voice had not been heard.

“Katharine, would you like to say something,” Bradlee asked.

Seated on an ottoman, Katharine Graham, who chaired the Washington Post (chairman was the title then), did not even stand. She did not need to. The room leaned in, to borrow a phrase from the future.

“Oh,” she whispered with a withering sarcasm, “I just want to thank Abe for allowing Elisabeth to write.”

“Discreet Feminist”

Much about Kay Graham, the subject of an exhibition opening Friday at the New-York Historical Society, is contained in that moment. “Graham became,” the exhibition summarizes, “a staunch, if discreet feminist.”

She also became the defining news executive of her generation, man or woman, and built a Washington Post that played a central role in American media and culture, including as the yin to the yang of the New York Times.

That alone would justify an exhibition at a New York historical institution of this Washington icon. To this day, there are Times executives who bridle at the attention Graham received in movies, books — and in this exhibition — for her courage in publishing the Pentagon papers after a court blocked the Times from continuing to do so, as if sharing the heroism somehow diminished their accomplishment (then again, sharing was never core to New York Times culture).

The ultimate journalistic triumph of Katherine Graham’s Post was, of course, its unflinching pursuit of the Watergate scandal, in which it bested the Times, toppled Richard Nixon and encouraged a generation to pursue journalism as a means to hold public officials to account.

The interaction between the Post and The Times would alone justify an exhibition at a New York historical institution. Every evening the two newspapers would exchange front pages by fax machine, a physical manifestation of how the Times measured itself against Kay Graham’s Post.

Black and White Ball

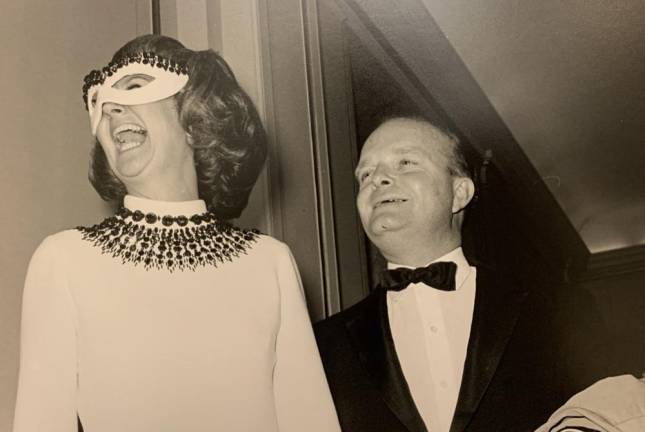

But Louise Mirrer, president of the New-York Historical society, points out that Graham’s New York connection runs even deeper. An entire section of the new exhibition, “Cover Story: Katherine Graham, CEO,” is devoted to a legendary New York event, Truman Capote’s 1966 Black and White Ball.

What is not always remembered about this soiree, convened by Capote to keep the spotlight on himself after publication of “In Cold Blood,” is that he named as the honoree Kay Graham, who had ascended to command of The Post, owned by her family, only three years earlier, after the suicide of her husband, the Post’s publisher, Phil Graham.

“Kay Graham’s story begins in New York, and the Black and White Ball at the Plaza was instrumental to her social status, so this history made good sense to us,” Mirrer explained.

Graham was far less known at that time than the Hollywood celebrities and European (and American political) royalty with which Capote filled the Plaza ballroom, the exhibition’s co-curator, Jeanne Gardner Gutierrez, reminds us.

This dramatically raised Graham’s public profile and showed her the power of hosting the great and the good, which she became well known for back in a Georgetown where political rivals still clashed in daylight and broke bread (or poured Bourbon) in the evening.

“She took that principal behind Truman Capote’s party and made it her own,” said Gutierrez. “She really changed her image after the black and white ball.”

Personal Transition

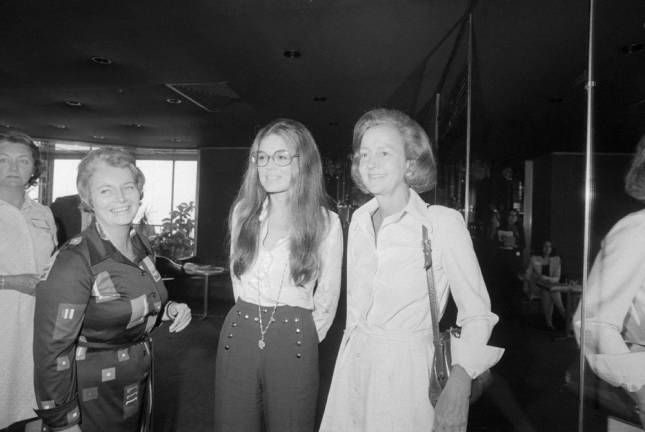

The motivating thought of the exhibition is expressed in the eulogy for Graham, prominently displayed, which Gloria Steinem delivered in 2001:

“As a transitional woman, with all the pain and late blooming that implies, Katharine Graham helped bring us out of a very different past. Because we are all in transition to an equality no one has ever known she will be a touchstone for the future.”

This notion of transition permeates the exhibition, in more ways than one.

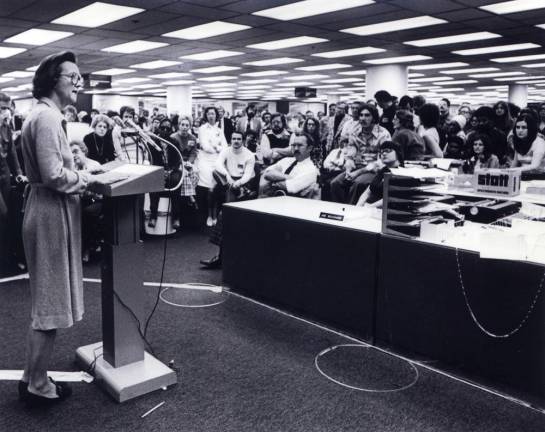

There is Graham’s expanding belief in her own abilities, which she doubted when young, even telling an interviewer a man could do her job better. Gutierrez notes that this personal transition was occurring as women were stepping into increasingly important roles across journalism, a movement of which Graham would become both illustration and enabler.

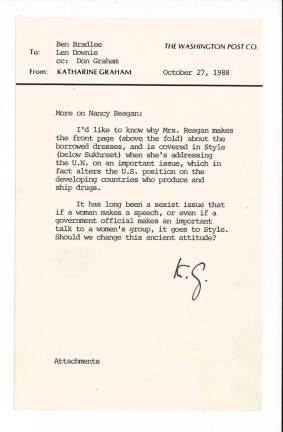

One striking artifact is a memo from 1988, in which Graham scolds Bradlee for ghettoizing in Style important news involving women, in this case, Nancy Reagan speaking at the UN on drug abuse.

“It has long been a sexist issue that if a woman makes a speech, or even if a government official makes an important talk to a women’s group, it goes to Style,” she wrote. “Should we change this ancient attitude?”

The exhibition coincides with an important transition at today’s Washington Post, which the Graham family sold to Jeff Bezos in 2013. Last week, Sally Buzbee of the Associated Press was named Executive Editor of the Post, the first women to hold the position.

“It certainly is very timely for us,” said Gutierrez.

But even as Kay Graham’s legacy of empowered women continues, another element of her history seems consigned to memory.

“Kay was a symbol of the permanent Washington, that transmutes the partisanship of the moment into national purpose and lasting values,” Henry Kissinger, the former Secretary of State, is quoted toward the end of the exhibition.

The exhibit hardly needed to point out that this permanent Washington is gone, even derided in many corners, and transmuting partisanship into national purpose seems, again, our greatest challenge.