Congestion Pricing Details Begin to Emerge as MTA Committee Wrestles with Exemptions

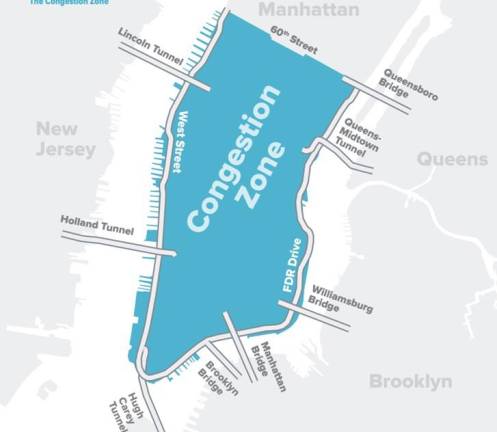

The congestion pricing plan is designed to raise revenue from auto traffic traveling below 60th St in Manhattan and funnel it to mass transit. Furious lobbying efforts are underway to get exemptions for various entities. The MTA’s little noticed Traffic Mobility Board is weighing options.

The daily struggle just to get subway and bus riders from here to there can easily overshadow the MTA’s new push for a larger reimagining of the city’s traffic and transit as congestion pricing rollout looms closer.

The toll on cars below 60th St. is still heading toward implementation in the spring of 2024. Traffic planners say the fee from congestion will discourage driving into Manhattan, reducing traffic by as much as 20 percent and thereby improving air quality and life in general. It will also throw off huge amounts of revenue that will go to finance bonds the MTA will use for capital construction. An MTA body called the Traffic Mobility Board met on Sept. 29 as part of a process to pin down the details.

Imagine Manhattan with 20 percent fewer cars. Or Harlem with a subway doing that rare thing of running from west to east and back again (rather than north to south) under 125th street.

Both these ideas and quite a few others were under discussion at MTA’s headquarters near the Battery.

The conversations were taking place at nearly the same time that the system was inundated by biblical level rainfall on Sept. 29.

One of their points was that if we don’t focus on it we will never organize the resources–billions of dollars in rebuilding money–that it will take. The MTA in its current plans is counting on this money, about $15 Billion, for about 30 percent of immediate capital spending.

While the legislature long ago approved this in principle, setting the details of who should pay what has been excruciating. Officials have said the daily fee could be as high as $23, but they seem to be honing in on something more in the $15 range more recently.

But that means they have to keep a tight reign on the exemptions, exceptions and discounts virtually everyone with a vehicle is lobbying for. Sorting that out is the assignment of the Traffic Mobility Board.

At the mobility board meeting, the motorcycle lobby burst into applause when an MTA official allowed that because trucks with six or more wheels would be charged twice or even three times as much as cars with four wheels it was possible motorcycles should only be charged half.

That choice probably won’t have a huge impact on the overall revenue. But other decisions have a big impact.

New Jersey has been screaming that the whole thing is unfair because their motorists already pay a big toll to get into Manhattan. So the mobility board is pondering a discount, but only a partial one, for those who use the Lincoln and Holland Tunnel, as well as the Queens Midtown and Brooklyn Battery Tunnels.

Yellow cabs and ride app car services make up a major part of Manhattan’s traffic volume. So they can’t be exempted, as they would prefer. The Mobility Board suggested the fee, between $1 and $2, would be imposed on the fare paid by each passenger, who after all is the one making the decision to enter Manhattan below 60th street.

The Mobility Board, which has more meetings to go, is moving at about the same pace as midtown traffic, although the reason is not gridlock but the political challenge of creating a system that is politically palatable.

The MTA said its immediate use for this revenue will be to complete its current capital spending program, which is heavily focused on repairs and improvements to the system, which in some places is more than 100 years old.

But at the same time they introduced a longer term vision that included what amounted to political carrots to encourage Albany and Washington to continue and even increase capital spending on the transit system.

While four dollars out of five will continue to go to improving the existing system, the officials also offered a list of new projects that might stir political enthusiasms more effectively than an improved signal system or rebuilding the train shed north of Grand Central before it falls in.

These new visions include the extension of the Second Avenue Subway across 125th street to Broadway, as well as a new line linking Brooklyn and Queens and the construction of a station for the number 7 line at Tenth Avenue, dropped in an earlier round of budget trimming.

“We are getting this on the table so that the discussion can begin about how much can we fund in light of the needs,” said the chair of the MTA, Janno Lieber. “That’s what is happening today. We are identifying the needs and let the discussion begin on how we are going to get there.”

All of that reinvestment, rebuilding and new building will cost billions. There is more money than their used to be from the federal government for infrastructure, although the MTA also argues it does not get its fair share based on the scale of its ridership.

Officials are hoping the conversation will be not just what should we build but how do we raise enough money to build a lot of these good new things while also making sure the system doesn’t break down.

“We are emphasizing the importance of rebuilding and improving the existing system,” said Jamie Torres-Springer, who runs construction for the MTA. “This is not new. 83 percent of our current capital program is rebuilding and improving the existing system. After you’ve taken care of those critical needs, the meat and potatoes, then you get to the additional potential for expansion.”

The Mobility Review Board’s success in creating an acceptable congestion pricing system could matter a lot in this going forward. Lieber noted that the congestion tolls were expected to push 100,000 passengers from cars into the transit system, which he said the system can easily accommodate as it still struggles to get back to pre-pandemic levels.

Even higher congestion tolls in the future would presumably push even more people onto mass transit, giving the MTA even more money to improve and expand the system.

“All we are saying today is that we’ve looked at potential proposals for expansion and evaluated them all on the same playing field, so that we and the public and stakeholders can make decisions,” Torres Springer said. “There is no commitment here to any kind of funding. We need to see how that goes with the priority being rebuild and improve the existing system.”

Or, as Lieber added, “we are saying to New Yorkers, you have an asset that is life or death for us as a region. That’s worth a trillion-and-a-half dollars. We all of us have to be responsible stewards. The MTA is giving information to make sure everyone understands what’s at stake...We are trying to make sure that everyone has the information. So we can have a much more robust public dialogue about what are we going to invest and what are we going to prioritize.”