Getting to the Heart of the News

In her first book, Emmy Award-winning broadcast journalist Jen Maxfield revisits the subjects of her stories

In her 22-year journalism career, reporter Jen Maxfield estimates that she has done over 10,000 interviews. They were all done in person, many times with people who had just experienced a tragic moment that would change the course of their lives forever.

“There have been a good amount of stories where, for one reason or another, I kept thinking about them,” she explained. “Whether it was the person I interviewed, or I’ll drive by the place the accident happened or sometimes I’ll have a dream about the stories.”

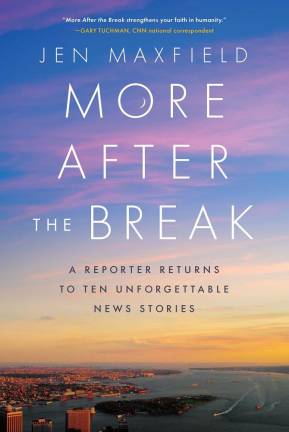

This is what led her to revisit 10 of those in “More After the Break,” which was released on July 12. Each chapter is dedicated to the news subjects she kept close to her heart and the new interviews she conducted with them years later.

The book opens with Paul Esposito, the then-24-year-old waiter who lost both his legs in the 2003 Staten Island Ferry crash. It continues with stories like that of Chris Clemente, the Harlem native who was attending the University of Pennsylvania when he was arrested for crack cocaine that wasn’t his and spent 14 years in prison under the Rockefeller Drug Laws.

Throughout her years working for Eyewitness News and currently, NBC, the individuals she interviewed touched her life, but she is always reminded that as a reporter, her work means something to them as well. In her home office, Maxfield has a Christmas card on display from a woman she spoke to after she lost her daughter and four grandchildren in a fire started by her son-in-law.

A Bergen County, New Jersey native and resident, Maxfield, 45, attended Columbia, earning her bachelor’s degree in political science and a master’s in journalism. Now, the mom of three, who still covered breaking news when pregnant, works as an adjunct professor there.

When did you know you wanted to be a journalist?

I was pre-med in college. My dad is a doctor at Columbia Presbyterian and so I always wanted to be like him. But I was very into sports growing up, so I wanted to be a sports medicine physician. That was my career goal ... so I went to Columbia and took a lot of math and science classes, but I did write for The Spectator. And I always loved to write and read. Then I saw a posting for an internship at CNN at the United Nations my junior year ... and I wound up interning with Gary Tuchman, a national correspondent for CNN. This was the best internship because he really let me learn ... Once I really got into the internship and realized how much I enjoyed the excitement and the creativity of broadcast news, I switched over to poli-sci and that was it.

Tell us the best and worst parts of your job.

The best part of the job, for me, is I’m an extrovert. I love meeting new people, talking to people, going to new places. I feed off other people’s energy so I do enjoy meeting new people and learning about different things. And just looking people in the eye and having conversations, I just really get a lot out of that and I also like to write.

The hardest part of the job, I think a lot of it has to do with some of these situations where you are in someone’s home and it’s the worst day of their life ... and you feel so badly being there. But I also feel a sense of responsibility that I’m there to tell their person’s story. So sometimes I think what’s even harder than doing that initial door knock and asking them for the time, is to leave. Because I feel the pressure of the deadline and I need to get the story out there to the viewers, but I also feel badly leaving people in that state.

I know there’s no typical day for you when you’re out reporting, but can you give us some structure to your routine?

It is true that there’s no routine, and as I write in the introduction, it’s like a Murphy’s Law of reporting. The day you buy new shoes and are wearing them on a story is the day you’ll be sent to some mudslide somewhere. But I would say that typically with certain things, you prepare in certain ways. I do keep things in my car, so I’ll keep rainboots, an umbrella, a warm jacket or hat in the wintertime. I always have food because I don’t like to be hangry on a story, so I’ll always have snacks, I’ll bring stuff for me and the photographer, because we just never know. Sometimes you can think you’re going to have a regular day and normal working hours and then something breaks and you’re on a scene for five or six hours and it’s nice to have granola bars in your bag for those days.

You interviewed Paul Esposito in the hospital two days after the ferry crash. What do you remember about that visit?

I remember how much he smiled and how much he laughed. And it was so hard for me to put that together with the young man who was lying in the bed with no legs. And the way he talked to me that day when we walked into his hospital room was like as though I had walked into the restaurant where he’d been working three days prior. It was just like, “Hey Jen, how are you?” Very casual and upbeat. I’ll never forget that. And also then interviewing in that news conference format that I write about, Kerry [the nurse from Wales who saved his life] and just thinking about what that scene must have been like on the boat. And when you think about how gravely injured Paul was and then you consider what she had to do, she had to steal the EMT’s gear bag to get him on the first ambulance. He one hundred percent would have died if she didn’t fight for him.

I thought an interesting fact you mentioned about your Hurricane Katrina assignment was how a gasoline truck came only to fill up news vehicles and an armed guard was there to make sure no residents, who were desperate for gas, interfered.

In some ways, I always think in a situation like that, about how lucky I am because I was going home in a few days. The circumstance that everyone in Mississippi was in, I was not going to live with. I told the story about the fuel truck because that seemed to encapsulate that idea that you got people waiting in line for 24 hours for gas and here we are getting it from a fuel truck. But if you don’t tell the story then people don’t see what’s happening around the country, and they’re not going to be able to help.

In your chapter “Friday Night,” you write about the interview you did with Corrine Nellius, a mother who had just lost her only daughter in a drunk driving hit-and-run accident. You said she was one of the people who inspired you to write the book.

She was the first one I called when I thought about writing the book. Her daughter, Tiffany Jantelle, was 23 years old and she went out with her friend and her boyfriend on a Friday night and as they were driving home from the bowling alley where they were, she spotted a dog in the middle of the road. It was a two-lane highway in Central New Jersey. And she was a huge animal lover. She used to tell people she loved animals more than people. She demanded that her best friend pull the car over and sat with the dog in her lap. And her friend sort of manipulated her car to illuminate Tiffany and the boyfriend stood to try to direct traffic but unfortunately a person who the judge later determined had been drinking, was driving his pickup truck way too fast and came around and ignored the boyfriend waving and yelling at him and ran her over and she died. And he got out, briefly, saw what he had done and drove away. And because he wasn’t apprehended until four days later, it was far too late to charge him with any sort of driving while intoxicated type of charge, so he was charged with leaving the scene of a fatal accident and wound up serving less than a year in prison.

By the time I interviewed Corrine in 2011, I did have access to social media and through the years, we’ve been Facebook friends. So it wasn’t as though I was constantly in touch with her, but I did have a window into how she was feeling ... and I just thought there was something there. And I thought people might perceive it as, “Oh, that happened a decade ago, she must be doing so much better.” But I’m not really sure that she is, and I thought there was a story to tell there about the relationship between the mother and the daughter and this notion that you still have a relationship with your person, even when one of them isn’t there.

Join Jen at P&T Knitwear Books & Podcasts on Orchard Street on August 2 for a book signing and panel discussion. www.jenmaxfield.com