the big question

Sea levels are likely to rise between one and two feet in the city by the 2050s. What does that mean? By the end of the century, more than one in 10 buildings in Lower Manhattan could be subject to monthly tidal flooding.

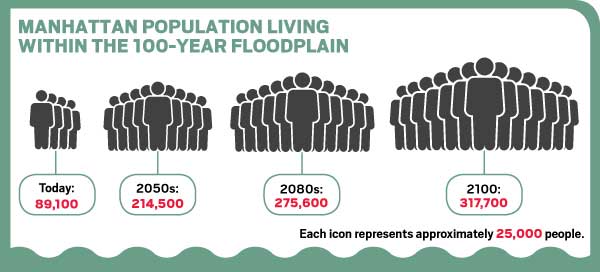

The city’s 500 miles of coastline will become increasingly vulnerable to extreme weather events as the 100-year floodplain — areas with an estimated one percent risk of being flooded in a given year — expands further and further inland as sea levels rise. The number of Manhattan residents living within the 100-year floodplain is expected to more than double by the 2050s.

The potential impact of federal policy changes proposed or enacted by the administration of President Donald Trump will exacerbate the effects of climate change and negatively impact public health according to experts. Under Trump’s leadership, the United States has announced it will withdraw from the landmark Paris Agreement on climate change, and his administration’s Environmental Protection Agency — headed by former administrator E. Scott Pruitt, who resigned in July amid a torrent of scandals, and Pruitt’s successor Andrew Wheeler, a former coal lobbyist — has proposed policies that would promote expanded use of coal and fossil fuels, and loosen regulations governing vehicle emissions, among other changes critics deem reckless, “anti-science” or worse.

New York is left to address issues of climate change without the support of the federal government. State and local officials have found themselves in a struggle on multiple fronts to mitigate the impact of federal changes proposed or enacted by the Trump administration.

New York has responded swiftly to many of the Trump administration’s federal policy shifts on environmental issues. Soon after Trump’s announcement on the Paris deal, both city and state officials vowed meet the obligations of the accord. The state attorney general’s office has led efforts to challenge EPA rule changes in the courts. And the new tenor from Washington has served as a stark contrast as the city continues its own efforts to address environmental issues and as climate change has emerged as one of the many political topics around which public mobilization has solidified.

Hundreds took to the streets in Foley Square to protest Trump’s June 2017 announcement on the Paris deal, after which City Hall and One World Trade Center were lit defiantly in green. Five months later, thousands of demonstrators marched across the Brooklyn Bridge to mark the fifth anniversary of Sandy and call for action on climate change, just weeks after Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico and much of the Caribbean. Later this month, as global leaders convene in New York for the United Nations General Assembly, the city will also host the 10th annual Climate Week, with a slate of events intended to push climate action to the fore of the international agenda.

In the last two years, the city has moved to aggressively reduce greenhouse gas emissions from buildings, adopted new guidelines requiring the design of city facilities and infrastructure to account for anticipated changes in sea level, temperature and precipitation, and announced it will divest pension funds from fossil fuel companies. These efforts take place as the city still works to recover from the impact of Hurricane Sandy, six years after it caused $19 billion in damage and lost economic activity, and continues to design and implement resiliency measures to prepare Lower Manhattan, Yorkville and other vulnerable areas for future storms and floods.

As Manhattan confronts an uncertain future, here’s what’s at stake:

AIR AND TREES

Downwind risks

In August, the EPA announced a proposal to replace the Obama-era Clean Power Plan, which aimed to significantly reduce carbon dioxide emissions in power plants, with a new policy that would relax federal clean air regulations that the Trump administration says unnecessarily burden the power industry.

The rule change would have a direct negative impact on New York City, said Judith Enck, who as EPA regional administrator during the Obama administration oversaw the agency’s work in New York and New Jersey. The risk centers on New York’s location, downwind of fossil fuel plants in Ohio, Indiana, Pennsylvania and elsewhere. New York’s own power plants are already subject to state-imposed emissions regulations that are more stringent than federal standards, but these rules do nothing to stop pollution from Midwest plants from blowing across state borders to New York. “Having EPA weaken clean air requirements leaves downwind states like New York very vulnerable,” Enck said.

Peter Iwanowicz, the executive director of Environmental Advocates of New York, said, “The Trump administration, in its zeal to prop up the coal industry, is aiding and abetting these power plants in not having to clean up their act, even when they know that the emissions from these plants are going to cause ecological destruction, air pollution, trigger asthma attacks and cut short the lives of seniors.”

While the EPA’s own projections estimate the policy change could result in up to 1,400 premature deaths each year by 2030, Enck said that well-publicized figure alone doesn’t capture the full scope of the policy’s potential public health impact. “It’s terrible to have unnecessary premature deaths, but what that number is missing is the number of people who will have nonfatal asthma attacks and heart attacks,” she said.

“One of the reasons why EPA was established by Richard Nixon was to deal with these cross-boundary issues,” Enck said. “New York State has sued out-of-state coal plants before, but the suits were based on these coal plants violating EPA regulations. So if you are weakening or eliminating the regulations, it makes the litigation much harder.”

The Trump administration’s potential changes to coal regulations follow the announcement of proposed rules that would freeze auto emissions standards put in place during the Obama administration and also challenge the authority of states like California to enact their own, more stringent tailpipe emission regulations. (California’s standards are followed by 13 other states, including New York.) “Not only would we get bad air to breathe, if the president is successful here, but we will get cars that drive fewer miles per gallon than we otherwise would, meaning we’re going to pay more at the pump,” Iwanowicz said. Over a dozen state attorneys general, including New York’s Barbara Underwood, have already announced their intention to attempt to block the coal and auto emissions changes in the courts if they are adopted. “You don’t just walk away from a successful program that a lot of states are relying on to reduce pollution and advance innovation in the automotive sector and not expect this to be tied up in litigation,” Iwanowicz said.

These potential clouds roll in just as the city announced that pollutant levels are down across the board since its air monitoring program began in 2008, an important step toward New York’s goal of having the cleanest air of any major U.S. city by 2030; planted over 620,000 new trees since 2014, which remove hundreds of tons of pollutants from the air each year; and enacted a permanent ban on cars in Central Park—a step that would have been all but unthinkable just a few decades ago.

WATER

Rainfall and flooding

Even if drastic emissions cuts were immediately imposed on a global scale, New York would still be left to contend with sea level rise that is “locked in” to our future by greenhouses gases already in the atmosphere. The city has already begun preparing for this new reality, but many areas remain vulnerable.

“Sandy was a form of shock therapy,” said Steven A. Cohen, the former executive director of Columbia University’s Earth Institute.

Since 2012, the MTA has installed marine doors on low-lying subway entrances to prevent stations from becoming inundated during future floods; Con Edison has fortified the East Side substation that flooded during Sandy and caused electricity outages in much of Manhattan; and the city has worked to upgrade infrastructure in flood-prone areas.

Work is still in progress — and funding is still being sought — for a number of consequential measures, including the Lower Manhattan Coastal Resiliency Project, which will seek to defend the downtown waterfront with measures such as temporary floodwalls that could be deployed before storms and raised earthen berms along the Battery.

Other storm surge protection plans are grander in scale. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is currently accepting public comments on a number of proposals to protect the region from coastal storms with new infrastructure, one of which would include a five-mile long barrier across the mouth of New York Harbor from Sandy Hook to Breezy Point.

Enck, the former EPA official, cautioned against a harbor barrier, which the Regional Plan Association estimated could cost $10 to $36 billion to build and between $100 million and $2.5 billion each year to maintain. “I think that is very ill-advised and the city should weigh in with the Army Corps of Engineers and say: stop wasting time on that multi-billion-dollar boondoggle and help us with real resiliency steps,” she said. “Walls on the land are fine to block water, but if you put walls in the water it just pushes the water other places and also potentially does permanent damage to the Hudson River.”

The myriad impacts of climate change extend beyond the oft-cited examples of sea level rise and increased coastal flooding. Instances of intense rainfall are projected to increase in the coming decades. In New York City heavy precipitation sometimes leads to a phenomenon known as combined sewage overflow in which untreated wastewater is discharged directly into the city’s rivers and bays. Continuing the New York’s tree planting initiative, which has added over one million new trees to the city since 2007, and creating and preserving green space to absorb rainfall will be crucial for preventing combined sewer overflow, Cohen said.

WHAT LIES AHEAD

Toward a sustainable, resilient future

The last two years have made it clear that even in the absence of federal leadership, state and local authorities will do what they can to address climate change and environmental regulation on their own. But will that be enough?

“To make a real difference, yes. To solve the problems, no,” said Rebecca Bratspies, the director of the CUNY Center for Urban Environmental Reform. “The reason we have federal regulations is that so many of the environmental problems we face are far beyond the capacity of one state to control,” and must be addressed on a national and international scale.

But New York City does have an important role to play, she said. By virtue of the city’s size and economic clout, policies enacted here have the potential to become widely influential.

“The systems that we work out, the laws that we enact and implement really can set the mark for what other places are going to do, because they’re looking to places like New York for models,” Bratspies said. The city mandate announced last year to cut fossil fuel use in buildings, which officials say will reduce citywide greenhouse emissions by 7 percent by 2035, for example, “is going to have tremendous implications for the city and state’s overall carbon footprint, and once it’s in place and up and running it also creates a model that other municipalities can copy in a relatively easy fashion.”

New York has set ambitious goals on climate change — both the city and state have signed on to the so-called “80 by 50” pledge to reduce emissions to 80 percent by 2050 — but meeting them will require aggressive action.

“There’s no other way to meet the 80 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions in the city or at the state level by 2050 unless we completely move our entire economy off of fossil fuels,” Iwanowicz, of Environmental Advocates of New York, said. “It’s just not possible to achieve an 80 percent cut otherwise.”

Bruce Ho, senior advocate with the Natural Resources Defense Council, said, “It’s become increasingly clear that the 800-pound gorilla in the room is transportation.” Federal changes on vehicle emissions may be disheartening, but they don’t prevent states and cities from reducing emissions by “improving our public transportation systems, improving our bikeable and walkable infrastructure, ensuring that there’s affordable housing near transit, and hopefully continuing to push the ball forward in the transition to electric vehicles, both through investments in the infrastructure and by setting targets and standards that will get us there.”

Cohen, of the Earth Institute, said that funding subway and bus improvements through congestion pricing is imperative. To the extent more buses and cars are electric and powered by renewable energy sources, all the better.

“Everything we’re doing to adapt will be made easier if we make this transition away from fossil fuels to renewable energy and mitigate climate change to begin with,” he said. “Everything else we’re doing is kind of putting our finger in the dike, hoping we can make these other changes before the really serious flooding begins.”

Cohen finds a few silver linings in the federal shift on the environment since Trump took office. One is the slow churn of the regulatory apparatus. “It’s going to take a long time for the changes in Washington to have any impact, and hopefully by then the policy direction will change,” he said.

Another is the kind of response Trump tends to inspire in his opponents. “What’s happening in Washington is not helpful at all,” he said. “But in a really kind of funny way, it may not be as bad as people think, because Donald Trump is a really unifying force. Everybody who is against him really gets active.”

That public response, and the extent to which it translates into concrete political action, will play an important role in determining New York City’s environmental future. Which is to say, New York City’s future.

INFOGRAPHICS: Caitlin Ryther & Christina Scotti

DATA SOURCES: New York City Panel on Climate Change; New York City Mayor’s Office; Natural Resources Defense Council; Regional Plan Association; New York City Parks Department