Echoes of the Past, Whispers of the Future

The Frick Collection's exhibition of a little known Renaissance master

The curators at the Frick Collection have a knack for uncovering geniuses of the past and starting them trending. Now it's Bertoldo di Giovanni's turn, and it was worth the wait to get to know this major, but relatively obscure, Renaissance sculptor.

"This show grew out of the fact that we have the only Bertoldo in the United States and wanted to know it better," said director, Ian Wardropper. "We ended up doing what is the first ever exhibition on this sculptor who was important not just as a maker of bronzes but as a link between the greatest sculptors of the 15th and 16th centuries. He worked for Donatello and was a mentor to Michelangelo." He was also the friend, house guest, curator and a favorite artist of Lorenzo de' Medici.

Co-curated by Aimee Ng, Alexander J. Noelle and Xavier F. Salomon, the exhibition brings together virtually all the extant known work of Bertoldo. It's a rare chance to see every piece, across several media and forms, by a major artist. More than 20 pieces fill the downstairs galleries, creating interaction between terracotta, bronze, and a polychrome wood sculpture of St. Jerome. The visual conversations are lively and extensive; definitive answers are fewer.

Not much has been known with certainty about Bertoldo. The Frick's team went back to original documents from the early 1500s, translating, transcribing and turning them into hypotheses about the artist and his oeuvre. But it wasn't just dusty old documents they found. They discovered another obstacle that prevented Bertoldo's name from coming down through history.

"Bertoldo has been primarily identified in connection with three of the great names of the Italian renaissance, Donatello, Lorenzo de' Medici, and Michelangelo," said Noelle. "It's partly due to Michelangelo that Bertoldo is relatively obscure today. Michelangelo, as he got older, fashioned himself as a divinely blessed artist, as self-taught. And, therefore, he tried to erase Bertoldo from his narrative. The founding art historian, Giorgio Vasari, also contributed to Bertoldo's downplaying, in his "Lives of the Artists," when he established Donatello and Michelangelo as the bookending titans of the Renaissance... What we've done in this exhibition is really celebrate the ingenuity and achievements of Bertoldo in his own right."

Contemporary Connections

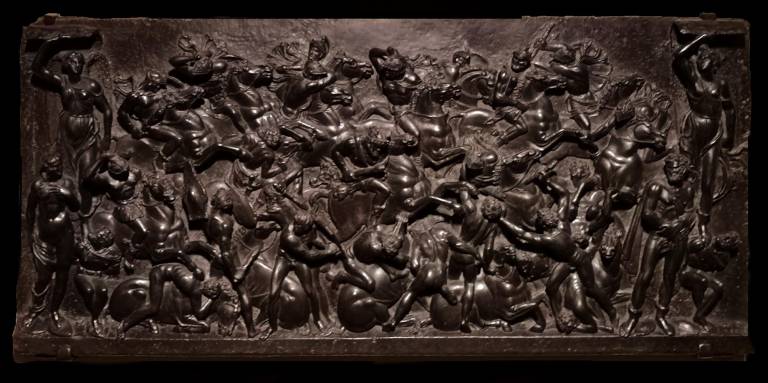

His sculptural achievements speak for themselves in complex and delicate but powerful statues, wall reliefs and medals, but the curatorial voices bring them out more fully. The first work encountered, at the base of the stairs, is Bertoldo's "Battle" relief. Salomon described is as "the main achievement of Bertoldo ... from the height of his career." The wall texts tell us that it was based on an ancient sarcophagus but reworked in a then modern way. Figures energetically twist across an undefined space. There's no ground under their feet that we can see, and gravity seems to have little effect on the horses and soldiers who recede, entangle, and then extend off the surface, coming deep into the viewer's space.

It conjures thoughts of the charged all-over rhythms of the Abstract Expressionists and the paintings with objects protruding that Eva Hesse made in the mid-1960s. Curiously, this quintessential Renaissance master's work brings lots of surprising contemporary connections to mind. A large ceramic frieze that once adorned the Medici villa at Poggio a Caiano, pings memories of Henri Matisse's "The Swimming Pool" at the Museum of Modern Art, with white figures across bands of cobalt. Designs passed along to other artists to complete (since Bertoldo had no workshop of his own) presage 21st century artists who utilize fabricators to make their art.

That seems to be the unique genius of Bertoldo – as conduit and connector. One large medal was packed with complex, tiny details intricately worked in bronze. On the reverse, where other sculptors might have just placed text or a coat of arms, Bertoldo works an entire Last Judgment scene. Blown up to 50 meters high, it's the same composition as Michelangelo's Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel. That more than suggests Michelangelo's recollection of his teacher's work.

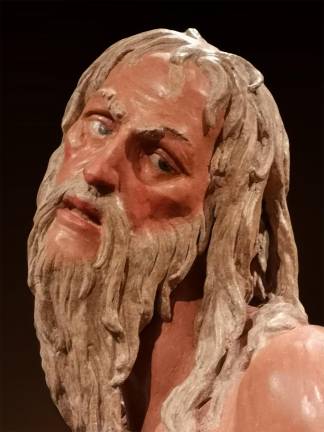

Pathos and Passion

Most spectacular is a life-sized standing figure in painted wood depicting St. Jerome. Again, it brings up questions of collaboration and inspiration, and again, the details are extraordinary. The pathos and passion of the penitent saint are expressed from his tormented gaze down to his knees, bruised from prayer. It recalls Donatello's Mary Magdalene commissioned for the Baptistery of Florence, but said curator Ng, "It just misses what Donatello seems to have been able to do in other sculptures."

When Donatello died, his final commission was recorded as having been completed by Bertoldo. So, who, exactly, sculpted this lifelike, suffering saint? "This is hotly contested," admitted Ng. "Some scholars are absolutely committed to this as a work by Donatello, and some are really sure about Bertoldo. This is why we bring these things together. To see how they suit each other."

Ng believes that new research, brought out in the splendid book that accompanies the exhibition, as well as the spotlight on Bertoldo, may result in new discoveries and attributions. It took more than 500 years for this artist to have his first solo show. Though most have never heard of Bertoldo di Giovanni, those who visit the Frick and get to know his work aren't likely to forget him soon.