A Stonewall 50 Time Capsule

With photos and letters, the New-York Historical Society and The Generations Project chronicle LGBTQ+ life and commemorate the uprising’s anniversary

For the next nearly five decades, a collection of memorabilia documenting LGBTQ+ life in the city won’t see the light of day.

Photos, letters and more are being stowed away as part of a time capsule collaboration between the New-York Historical Society and The Generations Project to honor the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising — while also offering future New Yorkers a glimpse into queer life and culture today.

“Let’s actually document our stories by making handwritten accounts of what we’re experiencing now and attaching photos to those experiences,” said Wes Enos, executive director of The Generations Project. He views the time capsule as an alternative to historic accounts preserved through social media.

Following a year-long delay due to the COVID-19 pandemic, items were stored by the New-York Historical Society in a box designed by Carlos Lopez. The Stonewall 50 time capsule is the first shared between the New-York Historical Society and The Generations Project, though both groups have previously undertaken time capsule projects of their own. By the opening date of 2069, the artifacts in this most recent capsule may be greeted by a very different world than that which New Yorkers are familiar with today.

Years In The Making

The Generations Project, a New York City nonprofit that centers LGBTQ+ storytelling through events and workshops, has created time capsules in the past — though with much shorter lifespans. Typically, they’re opened annually or every four years, in the case of a leap year capsule project. For the 50-year anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, in 2019, Enos decided to undertake something more “ambitious.”

“I’d always wanted to create a time capsule,” he explained, “that was actually going to be sealed for an extended period of time.”

While Enos had originally intended, alongside the New-York Historical Society, to collect contributions to the time capsule through the summer of 2020, COVID-19 pushed the sealing of the capsule back another year. A virtual closing ceremony, in Enos’ opinion, would have “defeated the whole purpose of the time capsule — that this is a physical entity,” he said. “This is something you can hold and touch.”

“A Story Of Triumph”

In addition to letters written during The Generations Project’s events, the New-York Historical Society amassed roughly 400 letters and photos, according to Marketing Manager Kathleen O’Connor. The organization called for submissions via mail or email and hosted an in-person event at the end of June with remarks from New-York Historical Society Vice President and Museum Director Margi Hofer, among others, to mark the sealing of the capsule.

The project will keep alive “memories of family, friends, those we’ve lost, night life, marches,” according to a written statement from O’Connor. “Each contributor has made their own history.”

Some contributors, Enos explained, have included their own interpretations of the aftermath of the Stonewall uprising in 1969. “Some people are submitting something that they think will set the record right,” Enos said, “and some people are making, probably, that narrative even more complicated.”

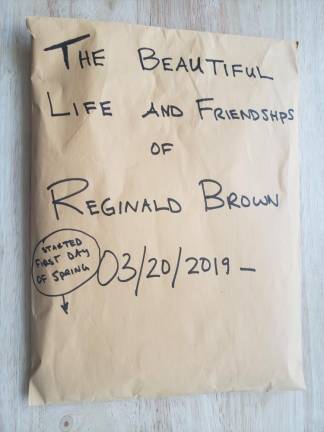

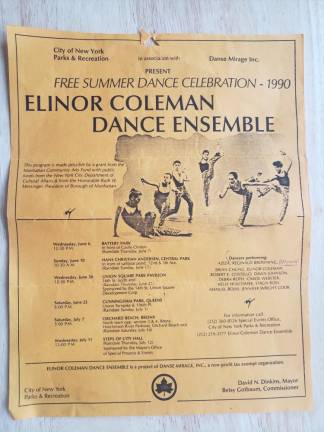

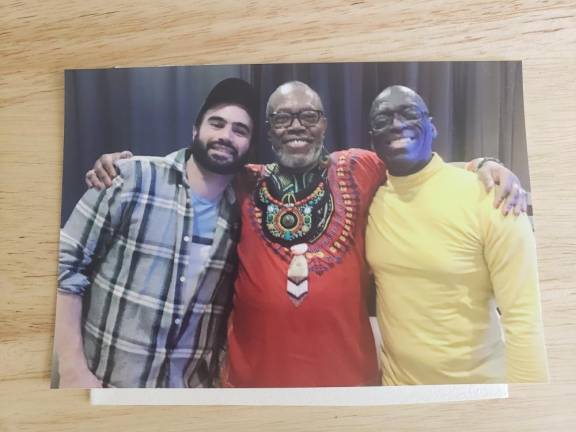

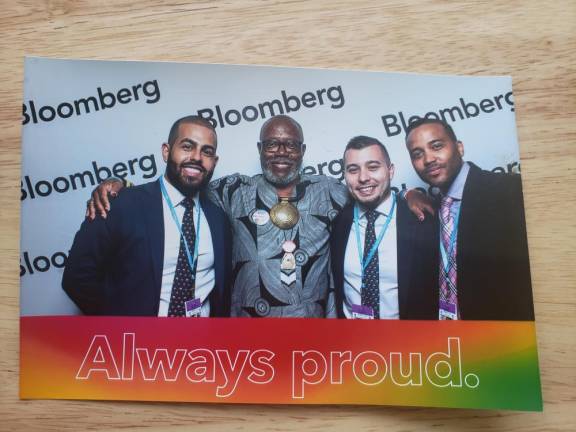

Others, like activist and retired dancer and performer Reginald Brown, submitted documents that address the topic of HIV/AIDS. Brown, who uses they/them pronouns, spoke about living with an HIV diagnosis at one of The Generations Project’s earliest events; now, they’ve included an envelope of photos and notes, as well as recordings of their past performances, in the Stonewall 50 time capsule so that future New Yorkers can glean a fuller picture of LGBTQ+ history.

“All the documentaries that I’ve seen about the early AIDS movement,” explained Brown, who’s been HIV-positive for over 30 years, “I don’t see hardly any Black people...so this is to correct that record, to say that, Hey, there were Black people that were there, too.”

“I have a story of triumph,” they added, “and not one of despair.”

The Test Of Time

Upon the 100th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, Enos hopes that someone who originally had a hand in the creation of the Stonewall 50 time capsule will be present to revive the artifacts from storage.

The New-York Historical Society has opened longer-term time capsules in the past; in 1914, the Lower Wall Street Business Men’s Association contributed a time capsule intended to be opened in 1974. It wasn’t opened until 2014, when a new capsule was then sealed to be opened 100 years later.

The Stonewall 50 time capsule has new technology on its side — it will be recorded and viewable via eMuseum, a tool that digitizes museum collections. And O’Connor suggested that the opening of the Stonewall 50 time capsule in 2069 might spur yet another project of its kind.

Much could change in coming decades; Enos sees climate change as a particularly relevant concern. But the “uncertainty” of the future has lent the project a greater sense of purpose. “A lot of us are creating content and putting things in the time capsule to set intentions to be better human beings over the next 50 years,” Enos said, “so we have a history to preserve and to look forward to sharing in the future.”

“All the documentaries that I’ve seen about the early AIDS movement, I don’t see hardly any Black people ... so this is to correct that record, to say that, Hey, there were Black people that were there, too.” Activist and retired dancer Reginald Brown